Category Archives: Jean Howard

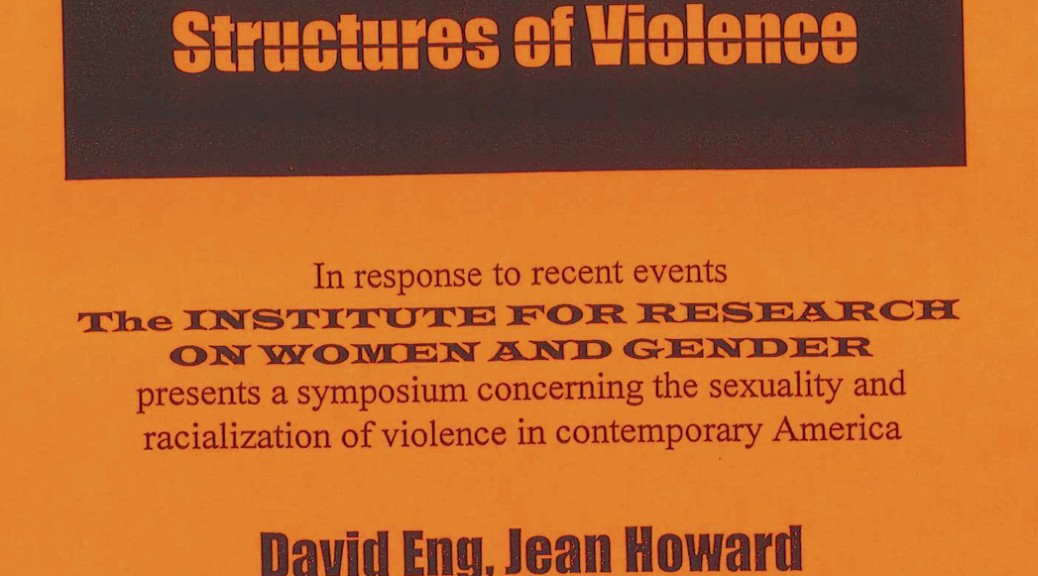

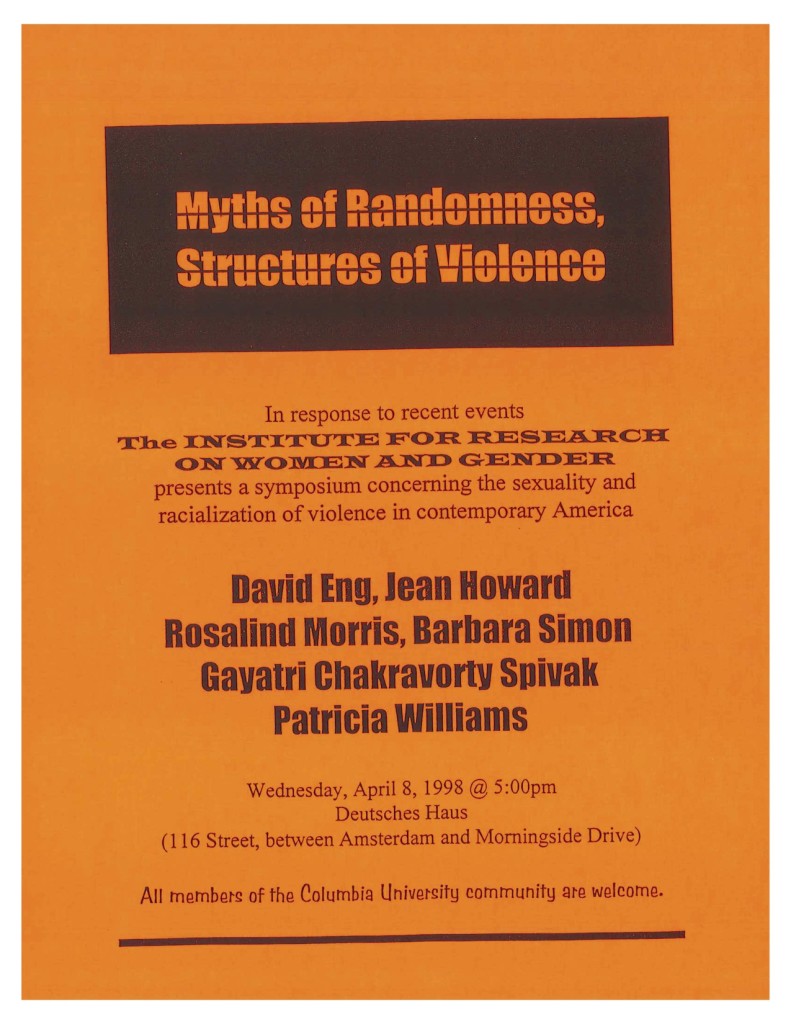

Myths of Randomness, Structures of Violence

“…it wasn’t clear how the relationship with Barnard was going to work out”

JEAN HOWARD

George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities

IRWGS Director, 1997-99

Q: How did you relate to Barnard?

Howard: Just fine. There was some tension, largely at the very, very early years of the institute, when we were very dependent on Barnard for courses, and it wasn’t clear how the relationship was going to work out. There were, at various times, competition and rivalry between Barnard and the institute. I’d say in the last ten to fifteen years, those have almost totally disappeared as we have learned how to each do certain courses, how to team-teach the introductory course that’s always done by a Barnard person one year and then a Columbia person the next. Gradually, we no longer see ourselves as rivals or fighting for students. It took a while to work that out. They had an evolved program, we had nothing.

“…the English Department was a place that was looking to the past, not the future.”

JEAN HOWARD

George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities

IRWGS Director, 1997-99

Well, I came to the Columbia English department, and I was shocked. It was a very hard transition in—I had imagined something that just wasn’t true. It was a place that was looking to the past, not the future. It was very male-dominated. I just wasn’t ready, having been at Syracuse for thirteen years where there were almost as many women on the faculty as men, it was very egalitarian, it was very democratic. We did everything by votes. Everything was written down, it was transparent. I got here and I couldn’t figure out how the English department worked. It seemed to work by a handful of older men making decisions. I think that’s actually how it did work. Of course, nobody really was getting tenure from below at that point, and so there was a huge divide between the junior and the senior faculty, and lots of misunderstanding, lots of suspicion. There were just so few women.

I was just always very self-conscious because you were always aware of your difference. I had a very small office on this floor, this lovely office I’m in now belonged to Ted Tayler, and I was in a very small one. But there were all men on this floor, and so you’d walk out and there would be this sea of men talking. You’d walk by, and they’d go silent. And I’m not making this up: a decade after I first came here, Fran Dolan was a visitor when I was at Penn, and she had the same experience. She’d walk out of the office and then all the men would fall silent. And it’s just––you felt like you stuck out. People were not mean to me or anything. There were many friendly people, colleagues. But the whole atmosphere was so charged with maleness that it was very hard, as a senior woman, to feel that you were really integrated.

Then, I found the gender institute very quickly. The first year I came, I was put on a committee, because there weren’t that many senior women, to choose the first head of the gender institute—not the first, the second. Carolyn Heilbrun had fought to have a gender institute set up at Columbia, and she had won that, and they’d given her a room, and that’s about as far as she got.

Then we were getting the first formal director and I was on that committee. Carolyn Bynum chaired that committee. She was new at Columbia. That’s the search that brought us Martha Howell, eventually, who became the first director. So in my second year here, I was working with Martha right away. She was in the early modern period in history. She’s a lovely, smart woman. And I began to help create the courses and create the curriculum and all the things that had to be done, and that was a glorious community. I had that as a very active, intellectual and also social space. That was my other [way of] coping. Then I had my family, and I had lots of friends in the discipline, so I wasn’t stuck in the English department for everything. But I tell you, the English department did not nurture me in that first decade. It was a very hard environment.

The English department I live in today is a fabulous department. I’m very happy in this department. I was not happy in the ’90s.

“It was called the Office for Diversity Initiatives…”

JEAN HOWARD

George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities

IRWGS Director, 1997-99

While I was in the Huntington, writing away on my book, Martha [Howell] and Alice [Kessler-Harris] and Lila [Abu-Lughod] and a group of people at the institute, Susan Sturm in the Law School, decided to lobby Lee [Bollinger] to set up some kind of position in the provost’s office where somebody would be responsible for improving the statistics on women and minorities on this faculty. And he needed this position—they said, you’ve got to have somebody dedicated to it. If it’s everybody’s responsibility, nothing’s going to happen. They persuaded him, and because I had done the pipeline report, they thought I could do it. So when I came back, weirdly, I came right back into this newly-created position, which was the most terrifying event of my life because I had never run such a thing. What was it to be a vice provost?

I knew from the beginning—I was going to run this with the help of other faculty, because I would need their legitimacy very badly, and I’d be their labor power since we didn’t have any office. So I got this office with a conference room, thank God. Best resource I ever had was a conference room. It was called the Office for Diversity Initiatives.

I set up this committee of faculty advisors to help me decide what we would do. We immediately said, well, one thing we’re not going to do is do a diversity action plan, because that will take a year or two years, and I have a drawer full of diversity action plans from every other university, and they all look the same. The idea is not to have the plan, it’s to do something. So we dispensed with the two years of doing a diversity action plan, and we just started to do action. Do initiatives, do things. We knew the first thing we had to do was get target of opportunity money so that we could start hiring and make the faculty believe that there were actually going to be more women in the sciences and more diverse people in the disciplines. We hired, or helped to hire, twenty-three or twenty-four in the three-year period. It was a fabulous run of exquisite hiring, all done with the faculty completely involved and completely vetting everybody. Nobody was ever forced to take anybody, it was always choice. That was the big thing.

But this committee was so visionary, it also knew that we needed a work/life office. We didn’t have one at Columbia. You can’t hire women in the sciences if you don’t have any provision better than we did for childcare, and all kinds of things. So we set up a work/life office, we set up a HERC, which is a consortium with a lot of area schools so you put all your jobs online so that if you have somebody coming in who has a spouse and needs employment and you can’t do it at Columbia, you have this huge bank of jobs. We set all that up, got that running. We set up affinity groups so that Black faculty coming into this place would, in the first month, be greeted by Black faculty from all over the university, so that they would feel that they were people that they could turn to. We set up these dinners where we train search committees about how you do proactive diversity searches. It was so great because faculty led them and faculty presented the data and presented the research that we had done on implicit bias, and all kinds of things.

We read, as a committee, all this research to figure out what we thought was good research that would convince the rest of the faculty that what we were saying was true, so it was all either data-driven or research-driven. All of this we did in the three years.

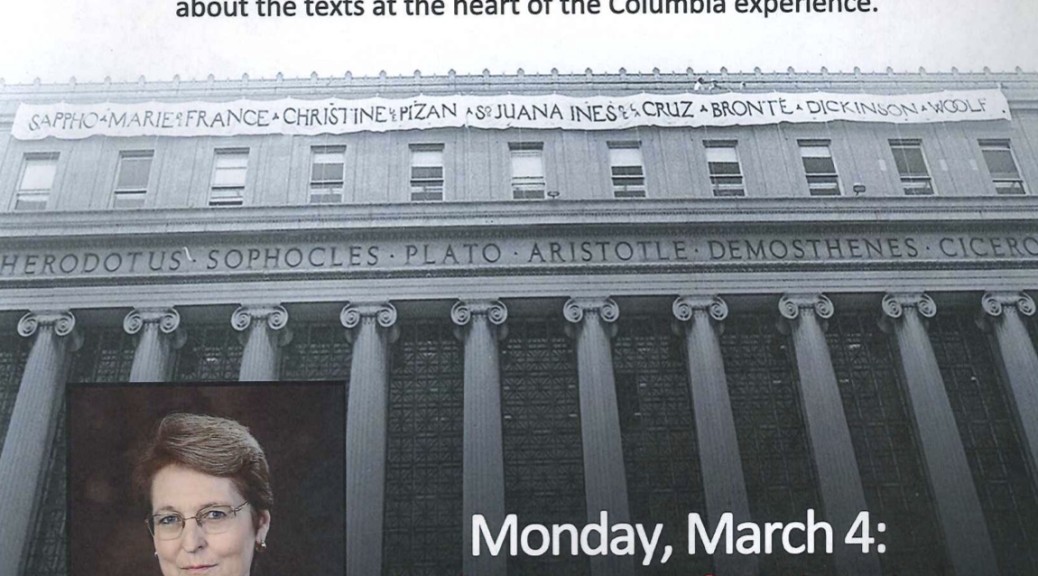

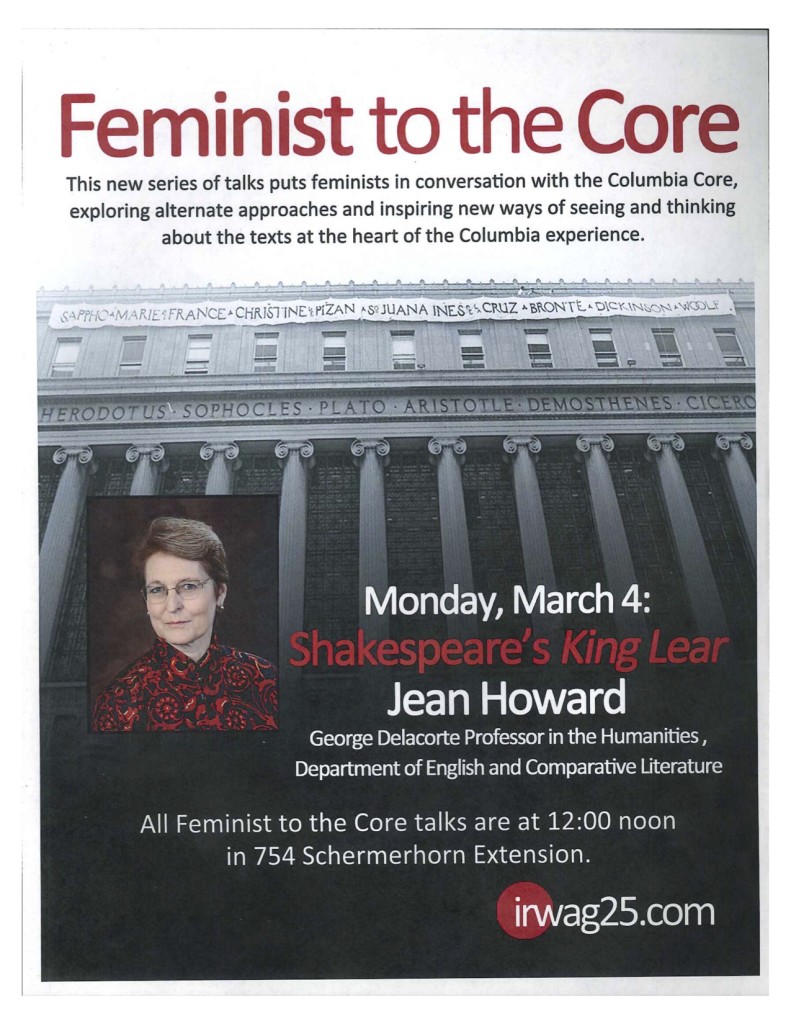

“Feminist thinkers were thinking with all those who had come before…”

JEAN HOWARD

George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities

IRWGS Director, 1997-99

Martha [Howell] and I decided we would teach a graduate course together, and one of the services we thought we would do for the university is—so many departments didn’t have any feminism at all. So we didn’t want a graduate program, but we wanted graduate courses that people could take from any department, and they’d mostly be team-taught, and we would give them training in feminist methodology. Martha and I boldly decided we’d teach the first one, and we put together what I can only describe in retrospect as the most ridiculous syllabus that I’ve ever seen, because it was so ambitious.

We were teaching Marx and Freud and Foucault, because they’re basic to feminist theory. But then we were teaching psychoanalytic feminism, and we were teaching Marxist feminism and we were teaching Black feminism and the syllabus was just overwhelming. And we had something like twenty students in there. The two of us, we were reading like crazy. Every week we’d call up and say, “Have you read the Freud yet?” “Can you do that part and I’ll do this part?” It completely exhausted us. It was an exhilarating course. So many of the students who took it—Gina Dent was in that one, Colleen Lye was in that one, and people who have gone on to be big scholars. It was completely exhilarating but it was very combative because it was the early days and everybody had their take. It wasn’t calm teaching. It was like, “Is that right?” Or, “Shouldn’t we do it this way,” or, “What about Black feminists?” It was, like, high-energy level as well as enormous intellectual challenge.

After that, we decided to striate the curriculum a bit, and we would have a more introductory course that would do certain key thinkers, and then we’d have more focused courses on special topics. Gradually, we got a graduate curriculum that had many pieces instead of trying to do the entire corpus of feminist work in one semester. But we remember that very happily, that moment.

Q: How did you come up with that title [Genealogies of Feminism]?

I thought we thought that feminism didn’t come out of nowhere, and people shouldn’t think that. Feminist thinkers were thinking with all those who had come before. We did owe a lot of prior people, not just people like Wollstonecraft, but Marx. And you couldn’t actually do feminist theory without knowing Marx, Freud, Darwin, you know, Burke—all these people had to be known. So that’s why the idea of genealogies. Feminism has a genealogy from the ‘70s and we must know that, but that feminism has a genealogy before that, in the lot of European traditions of thought, and you need to know those, too.