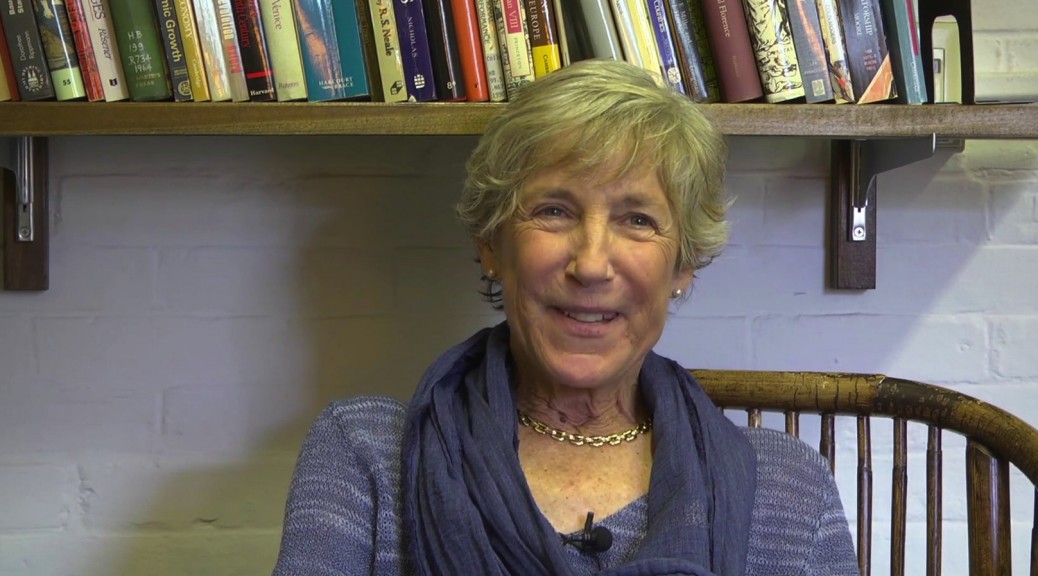

JEAN HOWARD

George Delacorte Professor in the Humanities

IRWGS Director, 1997-99

Well, I came to the Columbia English department, and I was shocked. It was a very hard transition in—I had imagined something that just wasn’t true. It was a place that was looking to the past, not the future. It was very male-dominated. I just wasn’t ready, having been at Syracuse for thirteen years where there were almost as many women on the faculty as men, it was very egalitarian, it was very democratic. We did everything by votes. Everything was written down, it was transparent. I got here and I couldn’t figure out how the English department worked. It seemed to work by a handful of older men making decisions. I think that’s actually how it did work. Of course, nobody really was getting tenure from below at that point, and so there was a huge divide between the junior and the senior faculty, and lots of misunderstanding, lots of suspicion. There were just so few women.

I was just always very self-conscious because you were always aware of your difference. I had a very small office on this floor, this lovely office I’m in now belonged to Ted Tayler, and I was in a very small one. But there were all men on this floor, and so you’d walk out and there would be this sea of men talking. You’d walk by, and they’d go silent. And I’m not making this up: a decade after I first came here, Fran Dolan was a visitor when I was at Penn, and she had the same experience. She’d walk out of the office and then all the men would fall silent. And it’s just––you felt like you stuck out. People were not mean to me or anything. There were many friendly people, colleagues. But the whole atmosphere was so charged with maleness that it was very hard, as a senior woman, to feel that you were really integrated.

Then, I found the gender institute very quickly. The first year I came, I was put on a committee, because there weren’t that many senior women, to choose the first head of the gender institute—not the first, the second. Carolyn Heilbrun had fought to have a gender institute set up at Columbia, and she had won that, and they’d given her a room, and that’s about as far as she got.

Then we were getting the first formal director and I was on that committee. Carolyn Bynum chaired that committee. She was new at Columbia. That’s the search that brought us Martha Howell, eventually, who became the first director. So in my second year here, I was working with Martha right away. She was in the early modern period in history. She’s a lovely, smart woman. And I began to help create the courses and create the curriculum and all the things that had to be done, and that was a glorious community. I had that as a very active, intellectual and also social space. That was my other [way of] coping. Then I had my family, and I had lots of friends in the discipline, so I wasn’t stuck in the English department for everything. But I tell you, the English department did not nurture me in that first decade. It was a very hard environment.

The English department I live in today is a fabulous department. I’m very happy in this department. I was not happy in the ’90s.