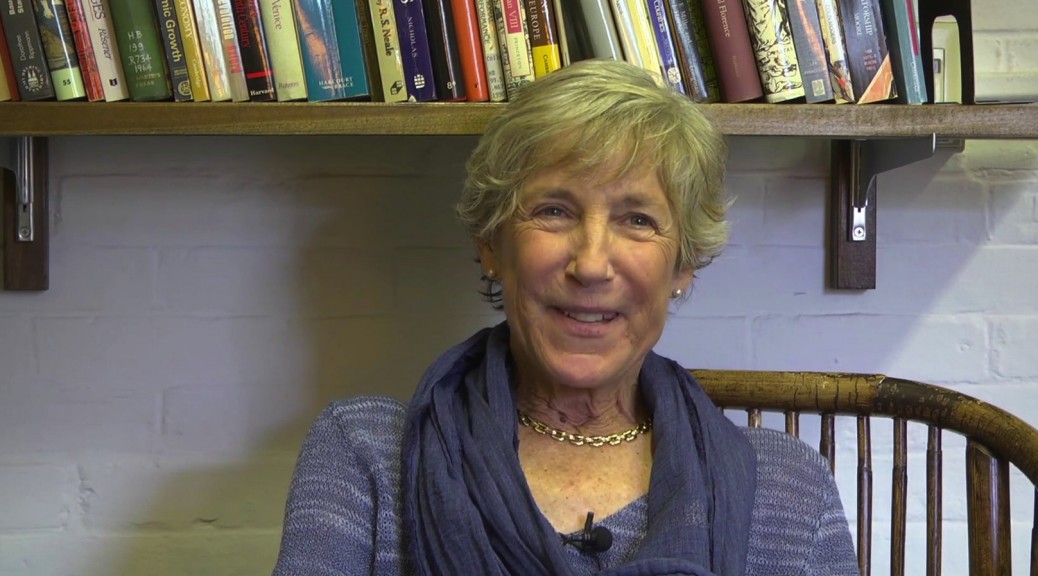

ROSALIND MORRIS

Professor of Anthropology

IRWGS Director, 1999-2000, 2001-04

All the student groups: it really depends on the cohort and how active the individuals are, how politically pressing the issues appear at a moment. Different issues grab the imagination at different times. Ethnic studies takes over it sometimes. Opposition to the war became a bigger issue than identitarian politics at one moment. In my opinion, IRWAG’s executive committee was always supportive, but the support came in response to student requests. It was very student-driven. There were certainly undergraduate students who were active in many ways. Maybe more active in the classrooms than in organizational ways, but there was a graduate student group that in some periods gathered, I think, almost weekly. They had theory reading groups, they had dissertation reading groups, and so forth. I think the support was largely providing a venue, largely providing a sense of legitimacy, perhaps promotion of activities. Across the board, the student-generated groups had support, but also were encouraged to assume a lot of autonomy, particularly in the early days when there really wasn’t any kind of stable faculty.

There were a couple of moments where things acquired a slightly different character, such as when we established the queer studies prize. That involved faculty much more directly, actually, in reading the work, and actually talking among themselves about what it is that we think ought to be the function of queer theoretical writing. Sometimes those committees would have quite intense disagreements, so sometimes it’s the desire to support the students that generates interesting theoretical reflections.

There were also some very difficult moments—for a long time we had a strong support and indeed some financial support from an administrator at Columbia by the name of Annie Barry. She joined those committees for a number of years. I can’t really ventriloquize for her of course, because she would have to express her own sense of what happened, but there was a period when it felt like we were getting so few, and such bad material, and so little interest by other faculty members that the prize almost collapsed. Basically, Annie withdrew herself from the process at that time. I think rightly so, but it had also to do with her status as an administrator in the adjudication process. If I remember correctly, I think that year we decided not to give the prize. We were so unhappy with what felt like anti-feminist work being produced within the queer theory that we were nonetheless teaching. You’d have to ask Julie Crawford about that, because she was very deeply involved and carried the prize forward into a renewed and much better form.

That was one bad year. Only one. Other years have been fantastic, and as I said, I think one has to assess that in terms of the vicissitudes of politics more generally. As I said, around the early years of the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, war and opposition to war took up a lot of energy. During unionization periods, that absorbed a lot of student energy. I haven’t been so involved of late, but my sense is that, for example, around the politics of gay marriage, with big deep splits within the community of IRWAG, the issue of civil rights has also been important. Those splits also ramified at the level of courses being offered. I think in one year, following a period of real activism around civil rights, in that same year there appeared to be a lot of courses on marriage, and maternity, and so forth, and some people felt, oh, what’s happening to IRWAG? But these things—one has to assess them in terms of a long arc, not just in the moment.