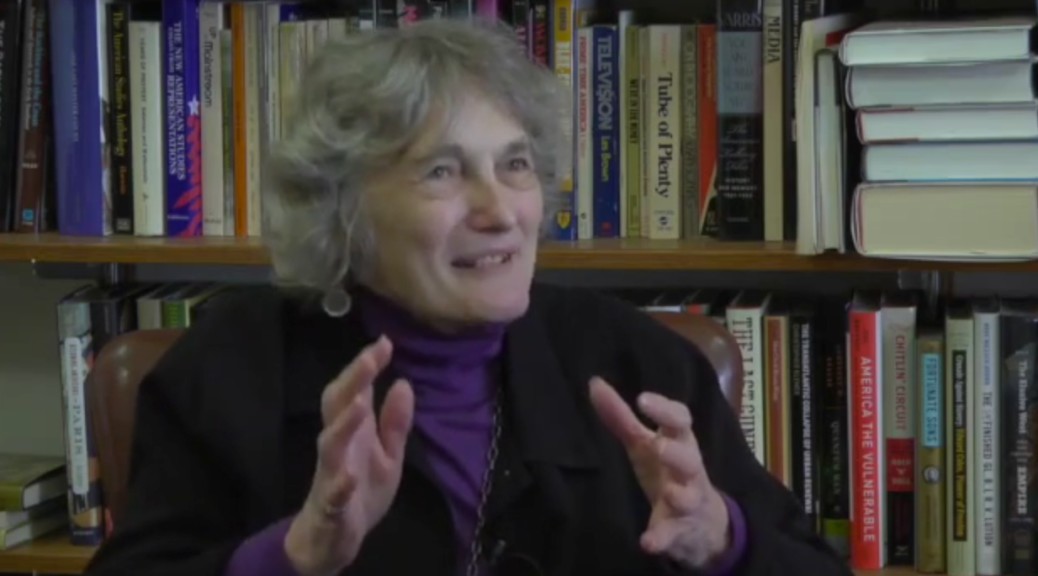

ALICE KESSLER-HARRIS

R. Gordon Hoxie Professor of American History in Honor of Dwight D. Eisenhower

IRWGS Core Faculty

In the early 1960s when I was still in graduate school I got involved with what was then an SDS, the Students for a Democratic Society project, a community organizing project. I think I was already pregnant at the time, in graduate school, and commuting and all that. So I was never deeply into it, but it certainly helped to shate my identity as an engaged historian. At the same time, I should note that historians in general looked down their noses at such activity. Presentism was what it was called, or relevant history. It was a dirty word. You couldn’t ask questions that grew out of the present situation. Our questions had to come out of some theoretically objective past. Women’s studies for me was a sort of release. Among other things it enabled me, along with others, to fight this notion of presentism being a bad thing. In the early 1970s there were struggles about whether a feminist history was not in and of itself a biased history and therefore not objective. “How could you be a feminist, doing history as a feminist, and yet be writing an objective history?” was the question.

Well, that’s background to your question because in the early part of the ‘70s—I guess it was ‘74, ‘75—I went off to Sarah Lawrence to work with Gerda Lerner at setting up the women’s history program there. I realized when I was there that the opportunity to work with the trade union movement, which came along at that time, was really the flip side of my interest in women—I was working on a book on women’s work, and I was into women’s history, but where was the labor background that I had begun with? After two years at Sarah Lawrence, I went to work for a trade union, District 65 of what’s now the United Auto Workers. It was then a Distributive Workers of America Local. Together with Bert Silverman and Murray Yanowitch, who had conceived the program, we worked at setting it up. My particular job was to be the onsite director of the program. The trade union had agreed to negotiate release time for the workers who came to classes at the union headquarters in lower Manhattan. We offered a bachelor’s degree sponsored by Hofstra University. We’d got special permission from the state to set up an off campus site. Most of the faculty were Hofstra faculty who taught in the union headquarters and we, the leaders of the program, were invited to sit in on the union’s executive committee meetings. We were very much in and part of the union structure, even as we remained, in some sense, people with academic heads. Negotiating, what you might call the community, the trade union and the university, was inevitably fraught. We found ourselves thinking about how we valued education and how to impart it to a non-traditional community. At the same time we recognized how much that community had to teach us and therefore struggled with how to involve it in the educational process. I have to say that that was one of the formative experiences of both my academic and my intellectual life.