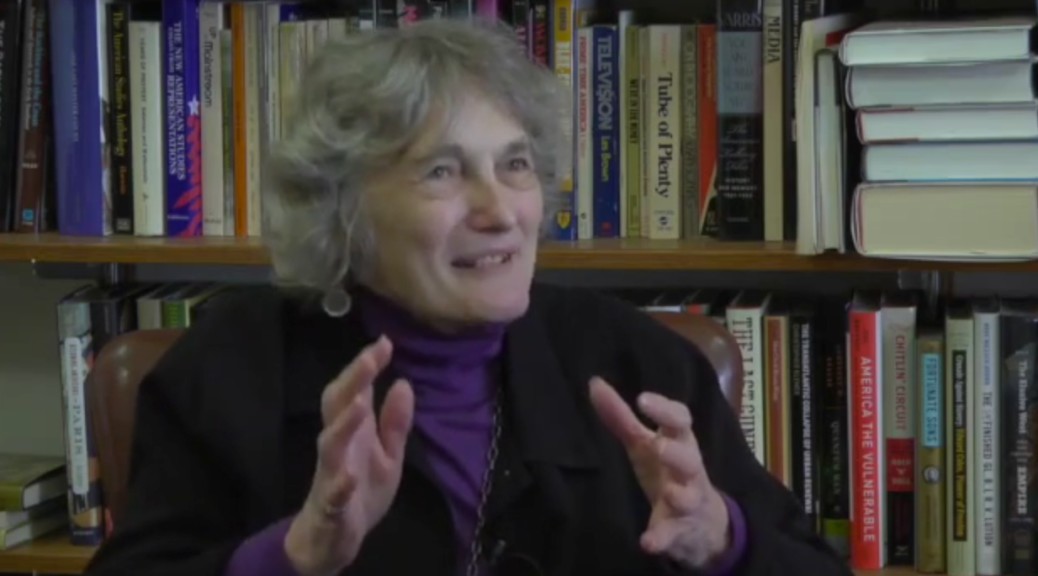

ALONDRA NELSON

Dean of Social Science, Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies

IRWGS Core Faculty

IRWGS Director, 2013-14

One of the really interesting things about IRWAG as a women and gender studies program is that it starts late. It doesn’t start until [1987]. By this point, you’ve already had the high water mark of second wave feminism. It happens because Columbia goes co-educational and you have, on campus, people like Martha Howell, and people who have been here a very long time in the feminist trenches without any kind of institutional space, but on their own doing feminist pedagogy, on their own doing feminist mentoring on campus and these sorts of things. Columbia comes to the institutionalization of women and gender studies late, at least ten years later than many of the other programs. I think the first program—I was at San Diego State last year at some point—the first women and gender studies program starts—it would have been feminist studies or women studies actually—in 1972. San Diego State lays claim to being the first one. Columbia is more than a decade later. That means that this program looks differently.

I think one of the things that might have been difficult for students is all of our work, at first glance, doesn’t look like feminist and gender studies work. I work on genealogy and what’s called kin-keeping and root-seeking. For me, that’s very much about thinking about norms around the family. All of this stuff around genetic genealogy assumes a heteronormative, normative family. That critique and that engagement with that conversation is part in parcel of what I’m always doing. Saidiya Hartman’s last book was on root-seeking in Ghana. Jean Howard works on Shakespeare. Roz Morris has been running a series on Africa and South Africa.

For the faculty, we are feminists. Everything that we do, our intellectual work, is always imbued with that. An example I use all the time is that when I was in graduate school looking at dissertations from the ‘80s and early ‘90s, there would be dissertations on labor or citizenship, name a topic, and there would be a gender chapter. I remember talking to people, older graduate students or people who are assistant professors, and that was the strategy. You do a gender chapter. But I come of age as a graduate student, as an undergraduate, where I don’t know how to think without always having a gendered perspective and a feminist perspective. That antenna is always up and active. It’s not isolated to a chapter. This book on the Black Panther Party’s health activism, there’s not a gender chapter, but there’s gender throughout the book in, I think, a matter of fact way. It’s less about the objects, like you mentioned some people work near history, far history, text, not text. Marianne [Hirsch] has worked on the family, but she’s also been working on memory. So I think if students don’t understand that history and they’re looking for a women and gender studies program that everybody’s work, every title, everything is “Gender and this,” “Women and that,” “Sex and this,” we’re just a little bit different. Part of that is because we come late. Women and gender studies is institutionalized late at Columbia, so Columbia is able to chart a different path.